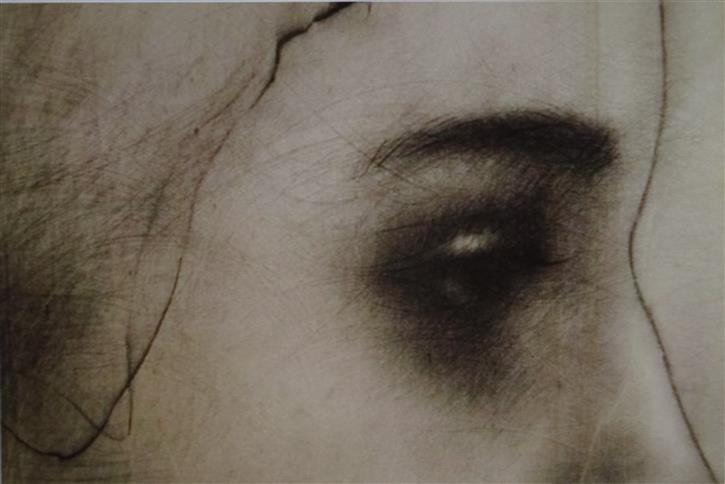

Portrait of a right eye. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

BN Goswamy

The paintings (miniature portraits that were exchanged) acted as tiny proxies to be kissed, pressed to bosoms and talked to when the subject was out of reach. But lover’s eyes were different. Instead of standing in for the whole person, they depicted just a minute feature. What’s more, they embodied a specific action: the gaze. It is the look of someone that the [lover’s eye] is a carrier of. It is the look that someone wants to imagine, and wants to feel as resting upon themselves.” — Hanneke Grootenboer in Treasuring the Gaze: Intimate Vision in Late Eighteenth-Century Eye Miniatures

Eye miniatures, also known as lover’s eyes, cropped up across Britain around 1785 and became en vogue… most were commissioned as gifts expressing devotion between loved ones. All were intimate and exceedingly precious: eyes painted on bits of ivory no bigger than a pinky nail, then set inside ruby-garlanded brooches, pearl-encrusted rings, or ornate golden charms meant to be tucked into pockets, or pinned close to the heart… As objects, lover’s eyes are mesmerising — and bizarre. Part-portrait, part-jewel, they resist easy categorisation. They’re somehow steeped in mystery. — Alexa Gotthardt

Even though we are still in the month of February, the Valentine’s Day, at least of this year, is long gone. For me to be writing about or around it now, therefore, must sound a bit odd. It is not, however, because I have, personally, ever been a great follower of that day — the day is, after all, named not after some celebrated lovers, but of Christian martyrs of long centuries ago; it is also not because of a natural tendency towards not saying the right things at the right time (following Munir Niazi’s famous poem: Hamesha der kar deta hun main?). It is because I chanced only recently upon the notice of an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art showcasing a delicious but long-forgotten lovers’ fashion that I knew nothing about till now. It goes back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries in England, and it was all related to exchanges between lovers, especially at this time of the year. Sending each other ‘eye miniatures’ was what it used to be called.

To this practice, or fashion, is attached a story that belongs to the history of British monarchy. It centres around the Prince of Wales, the young heir-designate to the throne of England, the future George IV (1762-1830). Young George was known, from the age of 17 years, to have been ‘rather too fond of women and wine’. In 1784, he fell desperately in love with a widow: a lady of rank, Maria Anne Fitzherbert by name. Their courtship, as records say, was, however, disastrous because royal laws forbade a Catholic widow from becoming the spouse of a monarch. All the same, the Prince proposed to her. Not seeing any future in this, and to save herself from avoidable controversy, Maria left the country and went to Europe. But would the Prince give up? He persisted, and sent her a passionate letter asking for her hand in marriage. This was no ordinary proposal, however, as they say, because with his letter arrived for her a ‘spellbinding gift’. “I send you a parcel,” the postscript said, “and I send you at the same time an Eye.” It was a painting of the Prince’s own right eye, ‘floating uncannily against a monochromatic background’. No other facial features appeared in the painting except for a ‘barely-there’ eyebrow. ‘All focus was on the composition’s core, where a dark iris gazed ardently behind a soft, love-drunk lid.’ Whether it was this most uncommon of gifts that melted Maria’s heart, or something else, one does not know. But it is known that the ‘star-crossed lovers’ wed soon afterwards in a secret ceremony. This time, however, another eye was painted — in Maria’s likeness — ‘which nestled into a locket for the Prince to treasure’. ‘No matter where his royal duties took him,’ the account ends, ‘George could open the jewel and receive his bride’s amorous gaze.’ The painter, in both cases, was the court miniaturist, Richard Cosway.

It is astonishing, however, how quickly having ‘eye miniatures’ made and sent caught on in British society. Not in imitation of a royal fancy alone — there is also the view, one needs to mention, that eye miniatures were in fashion even before the Prince got one made, lovers on their own seem to have realised the power of the image, especially when it also ensured communication in secrecy, in an ambience of alone-ness. Not everyone could afford the luxury of having eyes painted by a professional painter — photography had not been invented yet — but those who could, went for it. Somehow, as a historian of the fashion notes, British culture was “infatuated with seeing and being seen”. Further refinements set in, and these little miniatures started being framed and put on rings, pendants, brooches and lockets. Frames of diamond represented strength and longevity; those of coral were believed to protect the owner from harm; garnets stood for loyalty; and so on. Exhibitions today put an astonishing range on view. But one has to read the mood in those painted eyes: adoration in some, longing and lust in others, melancholy in still others. The gaze was the thing.

Speaking of the theme, however, one is reminded of the ‘eye’ in Indian literature and art. One speaks here not only of the types of eyes that poets have been singing about and painters painting for centuries here: maidens with sobriquets like kamala-nayani, mriga-nayani, khanjan-nayan, meenakshi, abound, and keep jumping from the pages of one romance to the next. And, as far as the gaze of the nazar goes, I find it hard to forget a session of qawwali I heard once. Nazar jhuk gayi to hayaa ban gayi, the leading qawwal began slowly, and then raced on: nazar tirchhi kar li, adaa ban gayi /Nazar pher li to qazaa ban gayi /nazar uth gayi to dua’a ban gayi.

It was magical; but of that magic another time. Perhaps.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.