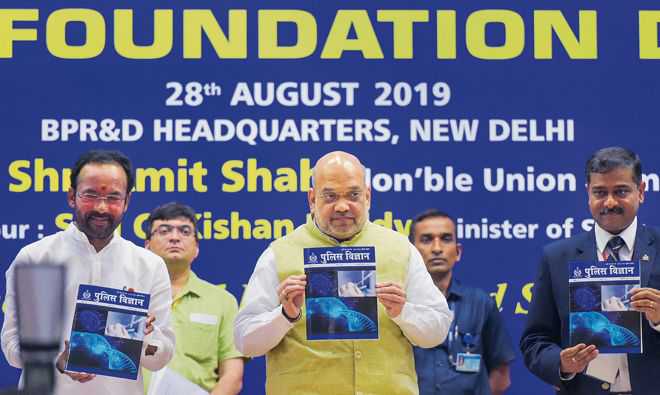

Envisaged: Revision of the IPC and CrPC following Amit Shah’s statement.

GS Bajpai

Professor, National Law University, Delhi

In pursuance of the recent statement by Union Home Minister, Amit Shah, the revision of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) and some other laws has been entrusted to the Bureau of Police Research & Development (BPRD). Criminal law reforms of the sort envisaged are rather uncommon as reforms and revisions in laws in this country have usually been preceded by certain crisis and urgencies requiring amendments. These limited amendments on earlier occasions, were based on specific needs and contexts, like the amendment of rape law provisions following the Mathura and Nirbhaya cases. Resultantly, the code has never been comprehensively revised.

Arguably, the state’s decision to make wide-ranging changes in criminal laws is intriguing, if not surprising. And the mandate this time is not restricted to any particular aspect of the IPC and CrPC. Rather, these laws are kept fully open for amendments. Prof Barry Wright dealt with the issue of the revision of the IPC on its 150th anniversary and found the task of updating the IPC to be difficult and the aim of perfecting it in accordance with the original principles to be highly complex. The thought of revising the IPC is an acknowledgement of the influence of extra-legal factors affecting the operation of the code. It is also about looking at those provisions that are irrelevant in the modern context.

Admittedly, the IPC has both structural imbalances and fundamental infirmities. The principles on which the IPC is based are free will, contractual premises and constitutional underpinnings. The robustness of the IPC requires substantive revisions to be based on these principles. The original premises and provisions of the IPC were differently oriented since the Constitution came much later than the code itself and, therefore, lacks its principled approach. The ensuing amendments spurred by the recommendations of the Law Commission of India and reports of other committees on criminal justice reforms influenced the amendments in the IPC by aligning them with the constitutional principles to some extent. Even so, a contentious mismatch between legal provisions and constitutional aspirations is visible at multiple places in the IPC.

Presently, the IPC contains 22 chapters and 511 sections. More than 40 per cent of the offences that are registered under various sections pertain to the chapters on ‘offences affecting human body’ and ‘offences against property.’ Surprisingly, even in today’s context, the offences relating to public order, sexual act and economic crime constituted only 3, 4.7 and 5 per cent, respectively, in 2016. This skewed distribution is a function of classificatory anomalies in the IPC which need reconsideration in the modern context.

The distribution of the number of provisions and the number of crimes registered under them also presents a definite picture about the direction and the nature of changes and revision needed in the IPC. One-third of all sections of the IPC pertain to only two categories of offences — against human body and property. The skew in the code can be gauged from the fact that out of 511 sections, 270 account for a mere 14.6 per cent offences. This data poses a question about the usefulness and unenforceability of such sections which relate to offences against the state, public tranquility, offences relating to coin and stamps, public health, document, public authority, false evidences, weights and measures etc. It is not my case that these sections are redundant, but that they require rephrasing to make them concise and relevant.

Such precision and relevance can be achieved only after much debate.

Amending laws does not mean mere addition, subtraction or revision of the existing provisos. It is as much about fundamental alterations as may be relevant in the fresh contexts; in revision of classification schemes; reordering of provisions and chapters; and rethinking of governing principles.

The IPC is a statement of criminal policy and, therefore, needs to spell out the way the state deals with the wrongdoing of people as well as the state through its officials. It includes the determination of the extent and type of behaviour to be criminalised. It also covers the penal policy of the state under which official sanctions are imposed in varying degrees and mannerisms of punishment, depending upon the penal policy of retribution, deterrence, restoration or alternative reactions to offences. Any change in the IPC, therefore, must be in conformity to the stated requirements.

Though the IPC was considered to be the major law of the land, the same is no longer the case. Major chunks of offences now form a part of special and local laws (SLL). These SLLs cover several types of offences, such as corruption, money-laundering, organised crime, drugs, domestic violence, sexual assault against children, offence against Dalits etc. These offences were once part of the IPC in some form or the other. Whereas on the one hand, branching them out to these SLLs has lowered the significance of the IPC, and on the other, it has created sharper processes and mechanisms to deal with them.

The trend of enacting specialised criminal laws has limited the scope of the IPC, raising pertinent questions, such as — ‘what is the future of IPC if this trend persists?’ and, ‘do we need to expand the IPC or continue to branch out special offences through SLLs?’

Another issue in the IPC is that of sexual offences. In the past two decades, sexual offences have received considerable attention. New offences, including stalking and voyeurism, have been created and the definition of rape has been widened. Even so, sexual offences under the IPC are located in the chapter on offences against human body as the code does not have any chapter on sexual offences. Such a specialised chapter is not only important in terms of its contextual significance but also because it covers a wide variety of offences within its ambit.

Victims of crime in India have been marginalised in the 150-year-long history of criminal law. Barring sporadic changes, the Indian criminal laws too have failed to keep up with the developments in the international victimology. The challenge for the IPC at this stage is to mainstream crime victims while developing the definitional understanding of offences even as the consideration for punishment must take into account the impact suffered by the victims as a consequence of the commission of a crime.

In a nutshell, any attempt to revise the IPC will have to focus on the following: principles like free will, general exception, penal philosophy, determination of punishment, including its quantum, would need to be considered; debate is required on the reorganisation of chapters, including further classification; the identification of offences, including their redefinition or decriminalisation; there is a need to prominently include the victim in the construction of offences; there is a need to revise the fine structure; and simplification of illustrations and language is required.